After posting the initial letters in The Burlington Magazine and Art Newspaper in these web pages we attempted to contact both Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, and although we eventually managed to find their addresses, neither has been willing to engage in any correspondence.

We also attempted to open a dialogue with Irene Gammel. We were aware she had been repeatedly asked to comment on Spalding and Thompson’s interpretation of her biography, but had refused to do so. This did not seem to us a particularly valid reaction to a request to verify academic research. We sent our original piece (Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief), to her personal and academic email addresses and by registered post to both her work and home addresses. We received no acknowledgment.

We post here the emails we sent to her at this time since they contain various questions that we hoped she would answer. None of these questions, which involve important factual verifications, have been answered, either privately or in the articles she has subsequently written, indeed, all of our emails were ignored.

CONTENTS OF THIS PAGE

Texts 2: Emails from Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie to Irene Gammel.

2a.Email of 26/11/19.

2b. Email to 9/12/19.

2c. Letter of 6/1/20.

2d. Email of 23/1/20.

Text 5. Irene Gammel. “Last word on the art historical mystery of R. Mutt’s Fountain?”, The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020.

Texts 6. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020.

6a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The last word? Not likely…”

6b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 5)

Text 7. Irene Gammel. “Plumbing fixtures: The vexing and perplexing case of R. Mutt’s ‘Fountain’” in The Burlington Magazine, January 2021.

Texts 8. Letter to The Burlington Magazine, January 2021.

8a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The Authorship of ‘Fountain’”, (reply to 7).

8b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 7).

Texts 9. Letters to The Burlington Magazine, April 2021.

9a. Julian Spalding. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text7).

9b. Glyn Thompson. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text 7).

9c. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “End of the Fountain controversy”, reply to Spalding & Thompson, 9a and 9b.)

9d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to 9a and 9b.

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 2b: The controversy re Duchamp’s “Fountain” (2)

9/12/2019, 17:13

Dear Irene Gammel,

I wrote to you two weeks ago re this, but may not have had your correct email address. So I am sending the same email again. In the meantime our article, with some minor updates, has been posted at https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/

I don’t see any great reason for us to be on opposing sides on this controversy, I hope you can agree that it is more a matter of establishing the real facts. These matter because Spalding and Thompson’s theories are now being taught as “real facts” in various higher education establishments.

Alastair Brotchie

Anyhow, here was our previous email:

(Text 2a)

Dear Irene Gammel,

We are writing regarding the accusations by Spalding and Thompson that Marcel Duchamp stole the Fountain artwork from Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. You must of course be aware that this accusation is based upon your biography of the Baroness (a misinterpretation of it in our view). We are assuming you may have seen the article in the Burlington Magazine by Bradley Bailey, which we believe finally refutes this assertion, and has thereby aroused new interest in this controversy.

We attach here letters from ourselves that will appear in the next Burlington Magazine and in the Art Newspaper, intended to summarise the facts of this matter and show that Spalding and Thompson are incorrect. So far as we know you have not expressed an opinion upon Spalding and Thompson’s accusations, and we feel that now would be a good time to do so. Next year, all of this material will be published both online and in a small book by Atlas Press.

We also have a few specific questions we would like to ask you, to clarify certain points of fact.

1. We have to admit we are not wholly convinced regarding your conclusions as to when the Baroness first met Marcel Duchamp. It seems to us there is little solid evidence that this happened before the Independents exhibition. We notice that the chronology in your subsequent book of her writings (Body Sweats, MIT, 2016) is ambiguous on this point, so we wonder if you have had second thoughts about this? It anyway seems to us very odd indeed that her artworks and poems to/about Duchamp should all date from between 1919 and 1921 if she had met him (and fallen in love with him as she writes) some time between three or five years earlier.

2. We are also not really convinced that the Baroness ever attended the salons at the Arensbergs. She was not exactly unremarkable, yet no accounts of them ever place her there. There are two particular points we would be grateful if you could comment upon:

— Please could you clarify the final phrase of the first sentence of this passage in your biography (p.168): “The Baroness was an early fixture in the Arensberg’s impressively large atelier salon — even when she was absent. The actress Beatrice Wood remembered her as a favourite subject of conversation among Arensberg, Roché and Duchamp, but these discussions ceased when Wood entered the room; the subject matter was too risqué for the young ingenue.” This can be read as “even though she was absent from it”, ie she was never there, but was just a subject of discussion. Or it can be read as “even when she happened not to be there”, which would imply she often was there. It would be very interesting for us to see a scan of Beatrice Wood’s original letter because as you know, the latter version, as it appears in your biography, contradicts completely what she says in her much earlier interview with Naumann, as published by Bailey.

— Also, in your note to this passage (note 24, p.432), you identify the Baroness as “Sabine” in H.-P. Roché’s Victor. When Dawn and I came to write the commentaries to this book as published by Atlas Press (Three New York Dadas and The Blind Man, 2012), we were rather disappointed to discover that the Baroness did not seem to feature in it, since she is of course a fascinating figure. But we could not see any connection between the sophisticated and “smartly” intellectual figure of Sabine and the eccentricities of the Baroness (we identified Sabine tentatively as Mina Loy). We wonder, therefore, how you made this identification, and why you state that Sabine/Elsa was a regular visitor at the salon, because she plays a minor role in this book and is only mentioned once as being at the Arensbergs? (We would be delighted if it could be established that Sabine was a representation of the Baroness, since the one occasion that she attends the salon, as recounted in Victor, happens to be when the group discuss Duchamp’s urinal at the Independents, so this would be further evidence that she was not involved.)

3. In Body Sweats you state that she had a relationship with Duchamp (p.20). This is a little puzzling. The Baroness was one of several who fell in love with him, but it was not reciprocated in any way so far as we understand. Is that what you mean by a relationship? There was a friendship certainly, but the word relationship is rather more charged? And Duchamp is bracketed here with William Carlos Williams with whom she did have a sexual relationship, so there is an implication here that would benefit from being clarified?

We realise there are some criticisms of your biography in our letters that will be uncomfortable, but you were not responsible for the cynical use made of it by Spalding and Thompson (cynical because of course the Baroness’s artworks represent everything they elsewhere attack).

We hope, therefore, that you are concerned, like us, to establish the truth or otherwise of these accusations and thus will welcome the opportunity to clarify your position in print, especially given your prominent position in academia?

There is quite a lot of material here, so we do not expect any sort of detailed immediate response, but it would be helpful for us to have some information regarding the queries above, since these are facts which are still in contention, and to know if you would like to reply to the longer texts in due time, so we can include any such reply in the published version of this correspondence next year?

Dawn Ades & Alastair Brotchie

*************************************************************************************************************

The following month we sent this letter with the printed versions of our text in the mail (text 2c):

*************************************************************************************************************

ATLAS PRESS

6.1.2020

Dear Irene Gammel,

I have been trying to contact you since November last year concerning certain interpretations of passages in your biography of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Email has proved ineffective so I am sending this to your personal and work addresses.

Myself and Dawn Ades are the authors of an article on “the Fountain affair” which appeared in last month’s Burlington Magazine. I enclose an updated version of this article, which has also been posted at https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/

I don’t see any great reason for us to be on opposing sides in this controversy, I hope you can agree that it is more a matter of establishing the facts and discarding speculation and prejudices. The facts matter because Spalding and Thompson’s theories are now being taught in various higher education establishments, and as an academic yourself this must concern you?

New evidence has appeared since the publication of your biography, and this surely deserves comment on your part. It is no dishonour to change one’s mind in the light of new evidence — quite the opposite, and all the more so when the reputation of an important artistic figure is being unjustly slandered in unnecessarily insulting language? These are the characteristics of “fake news”, which I am sure you agree should be fought in the arts as vigorously as in politics. You are in a unique position to do that on this occasion, whereas silence is likely to be interpreted as condoning this state of affairs.

Please be in touch, and we would be delighted if you would eventually contribute to the book which will contain all the documentation relating to this “affair”, including this correspondence.

Alastair Brotchie (and Dawn Ades)

*************************************************************************************************************

We wrote again a few weeks later (text 2d):

*************************************************************************************************************

Duchamp and the Baroness: update

23/01/2020, 12:45

Dear Irene Gammel

We are disappointed not to have heard from you, but perhaps we may do so soon? We sent print-outs of our article by registered post to both your home and university address. They appear to have been delivered.

We are especially keen to see the original of the letter from Beatrice Wood to the Baroness’s daughter. Perhaps you could tell us where this document is located, your book does not give this information?

This note is to let you know that the article on the Atlas Press website has been updated (https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/), and that the following letter will appear in the next issue of The Art Newspaper:

Alastair Brotchie & Dawn Ades

*************************************************************************************************************

Again, nothing. The letter of ours referred to here is text 4 on the previous page. (The location of the critical letter by Beatrice Wood remains unknown except to Professor Gammel, and we still do not understand why it was paraphrased rather than cited.)

At this point it seemed to us the only thing left to do was to appeal to her editor at MIT Press and in April 2020 we wrote to him suggesting that “is not the academic reputation of MIT Press somewhat at stake here, when one of its authors will neither defend her book nor admit that one of its central theses is incorrect?”

In May 2020 we were informed by her editor that Professor Gammel would indeed break her long silence, probably by July, but it took a little longer than that. This was her response, in The Art Newspaper (September 2020):

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 5

*************************************************************************************************************

The Art Newspaper gave us space for a brief reply in the same issue:

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 6a

“The last word? Not likely…”, The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020.

Dear Art Newspaper,

Unfortunately, Gammel’s much-awaited comment on the Fountain “controversy” is not the last word on this matter, because she continues to maintain her impossible position that the Baroness may have been involved, and because she makes no serious attempt to answer any of the questions raised since her book appeared in 2002.

Fountain is a readymade, and everything we know shows that Duchamp arranged for it to be submitted via his close friend Louise Norton. Bradley Bailey recently discovered an unpublished note in which Norton categorically attributed Fountain to Duchamp and also stated that he had “sent [it] in”. Norton’s statement is critical (see https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/ for a transcript). Gammel simply ignores the first part of it in order to make the somewhat absurd observation that the documents “exclude Norton as a candidate for shipping Fountain”. She had no need to “ship” it anywhere; Duchamp simply required the use of her address for the submission.

Thus if Fountain’s label had Norton’s address on it, and Norton said that Duchamp submitted it, and that she never knew the Baroness, what possible role can the latter have played? Perhaps Gammel can suggest one? Perhaps she can even supply a smidgeon of documentary evidence for it? We believe that a respected academic who casts doubt on an attribution as important as this — Fountain has been considered the most influential artwork of the last century after all — should have a few sourced and documented facts to hand. So where are they? We repeat: what facts connect the Baroness to Fountain?

There are many deliberate distortions of fact and interpretation in Gammel’s letter, and a lot of irrelevancies — all serve to disguise the fact that Gammel has once again avoided replying to this question, and until she does so the only real “mystery” here is one that she has summoned out of thin air and wishful thinking.

Dawn Ades & Alastair Brotchie

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 6b: Response to Gammel text 5.

We were exceedingly disappointed that Gammel had not taken the opportunity to concede that her supposition regarding the Baroness had been proved incorrect by evidence that was not available to her at the time she wrote her book. Not only that, rather than bringing clarity to the debate, she used this article to further obfuscate the whole affair. Since we were given so little space to reply, we do so here and apologise for having to repeat ourselves. Gammel, like Spalding and Thompson, tends to repeat her assertions even when they have been disproved; a common strategy in politics, but it is rather depressing to find it in academia, let alone Art History!

Paragraph 3. (Neither the Baroness nor her friends ever associated her with Fountain) We are in full agreement that the factors cited by Spalding and Thompson make it “problematic” that Duchamp appropriated an object by the Baroness. We are at a loss to understand why they are not equally problematic to Gammel’s claim that the Baroness was involved in any way with Fountain.

Paragraph 4. “Duchamp and Freytag-Loringhoven were friends”. Indeed, but were they friends at the time of Fountain? There is no proof at all of this, and in subsequent articles she appears to have dropped this claim. The rest of this paragraph is irrelevant as it concerns later events (a tactic Gammel often employs).

Paragraph 5. “Several newspapers reported that Fountain came from Philadelphia.” The text by Biddle is the first piece of evidence that connects the Baroness to Duchamp. It may seem nit-picking to suggest it does not mean they had actually met or were friends. Biddle actually writes “Spring 1917” and the Baroness had been in Philadelphia since January so it is difficult to see how she played any role in Fountain from such a distance, especially given her well-documented poverty at this time. There are no known letters betwen her and Duchamp. However, this phrase is quite extraordinary: “The fact that their love was unconsummated only… etc.” It is obvious that the Baroness fell in love with Duchamp since she repeatedly asserted so (in 1921), it is equally certain that he was not interested; there was no “their”. At the time he was having an affair with Louise Norton as Gammel herself states in paragraph 9.

Paragraph 6. Stieglitz did not surmise the person involved was “young”, he stated it, and assumed it was Wood. He seems not to have known of Louise Norton. But why assume the urinal was “shipped”, this is part of the Spalding and Thompson narrative and completely unproven. Duchamp said he bought the urinal in a store, it didn’t need to be shipped anywhere by anyone.

Paragraph 7. Finally we get to Louise Norton. Instead of accepting that Bradley Bailey’s new evidence makes her account impossible, Gammel either deliberately misrepresents it, or simply does not understand its significance. Neither is acceptable, although the second may be excusable. It was not the fact that the label bore Norton’s address that he first “presented”, this had indeed been well-known for some time (although Gammel relegated this information to an endnote in her book, as we have previously noted). Bailey discovered an unknown interview and unpublished article in which Norton stated that Duchamp was the author of Fountain and that he “sent it in”. And again, no shipping was required, and there was no “mystery person” only an address on the submission label that could not be Duchamp’s own since that would rather destroy the point of a pseudonymous submission (!).

Paragraph 8. It is an amusing notion that Duchamp chose Fountain for its masculine aspects as part of “an important strategy for its long-term acceptance and presence in museums” given that he then barely bothered to mention it for some 40 years — a remarkably patient “strategy”. This process, according to Irene Gammel, was to be completed by “aestheticizing what would come to be known as Fountain over the course of the 20th century” — again, it was always “known as” Fountain, the title was on the label, but more to the point, this statement shows that she is unaware of what Fountain signifies and thus why it was indeed voted “the most important artwork of the 20th century” (paragraph 1). Fountain is a readymade, an object chosen for rigorously non-aesthetic reasons to demonstrate that art is based, in the end, on the artist’s choice, thus the significance this work acquired with the arrival of conceptual art some 40 years later. It is baffling that someone could be making these claims about Fountain without understanding its rationale, which Duchamp explained many times. This aspect of Gammel’s misapprehension is covered in more detail in our reply to her next article in The Burlington Magazine (below, text 8a).

Paragraphs 9 to the end. What is one to make of these clumsy descriptions of the relationships between Norton, Wood, Roché and Duchamp, etc? Gammel appears to blame Duchamp for refusing to have an affair with Wood when he was already involved with someone else? She must have read Wood’s autobiography? (Wood and Duchamp remained close friends for life.) Gammel has Duchamp ridiculing people, brushing them off, blaming them for things. Not one of these life-long friends of his have suggested he ever acted in this way. Norton losing something Duchamp did not particularly value is given some sort of moral significance (nearly all the early readymades were lost, mostly due to Duchamp’s negligence, and he showed little concern about this). In the penultimate paragraph she repeats the claim that “we should not dismiss the Baroness as a candidate for having submitted Fountain” when this is precisely what the new evidence from Bradley Bailey means we should do. It is no good making such a statement: she has to explain why the new evidence does not make this impossible. There is only a mystery here if one does not accept the simple narrative that Duchamp bought the urinal and submitted it pseudonymously in order to liven things up as he had done in the Armory Show four years before, and Gammel has failed to show any reason to doubt this version. As for the concluding paragraph, this seems to be all smoke and mirrors, and we suggest an account of Fountain’s “inherent social dimensions” should be based upon simple criteria, such as an understanding of the intentions behind it, and thus why it is considered important in the history of Western modern art. This is missing from her account as it stands.

And she might like to answer some of our specific questions?

*************************************************************************************************************

This was followed by a second article in The Burlington Magazine (January 2021), that covered much the same ground, and avoided the same inconvenient truths and questions.

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 7

*************************************************************************************************************

Again we were given a small space to reply:

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 8a. Response to Gammel, text 7.

“The Authorship of ‘Fountain’”, The Burlington Magazine, January 2021.

Professor Gammel’s biography of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven successfully brought an extraordinary and unjustly forgotten poet and artist back into history. Unfortunately, in also trying to give the Baroness a central role in one of the most influential episodes in the history of modern art, she triggered a campaign to claim Fountain for the Baroness. Gammel here at last distances herself from the attempt by Spalding and Thompson to re-attribute Fountain and discredit Duchamp, but still seeks to link the Baroness to Fountain. In later editions of the biography she corrected some of her original mistakes, such as claiming (‘metaphorically’!) that Fountain was actually exhibited, and that Duchamp told his sister a female friend ‘sent him’ the urinal. To keep the Baroness in the picture, she now emphasises the collaborative nature of the episode. This, however, is well known and neither needs nor points to the Baroness’s involvement in any way.

None of the ‘pertinent details’ listed by Gammel support her claim with reliable evidence, nor do they add up to a plausible reason for changing the now well-documented account of Fountain’s genesis. The only ‘fact’ that connects the Baroness to Fountain is the report in a popular newspaper, which no one has ever mistaken for a newspaper of record, stating that the supposed artist R. Mutt lived in Philadelphia, as did the Baroness. That is the totality of the evidence, everything else is surmise and conjecture. The collaboration of Stieglitz and others such as Norton and Wood is well known and does not further her case. And it was a simple consequence of Duchamp’s pseudonymous testing of the ‘jury-less’ New York Independents exhibition, rather than a collaborative gesture aimed at ‘undermining traditional notions of the singular artist genius’. It seems pointless to go on arguing that the ‘female friend’ of Duchamp’s involved with Fountain was not Louise Norton. Although there are unknowns around Fountain that have fuelled groundless speculations, when Gammel here accepts that Norton, whose address was on the submission label, stated that Duchamp was Fountain’s author and that he had sent it in, she is accepting that these are now the established facts. No role can then be envisaged for the Baroness.

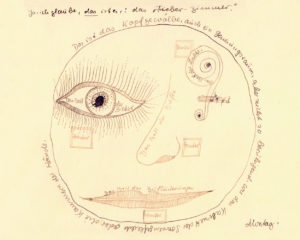

The Baroness’s unrequited passion for Duchamp was very public during the brief period of her celebrity in New York c.1918-22. Her association with Duchamp and Man Ray featured prominently in the single de luxe issue of New York Dada (1921). There is great pathos in her painting Forgotten… made after her return in poverty to Berlin. It is totally plausible that this was a call for help addressed to Duchamp as well as Bernice Abbot. She identifies Duchamp with those objects for which he was famous, pipe and urinal: which tends to confirm Duchamp’s authorship.

We cannot agree, therefore, that her “book still provides the most accurate representation of the evidence we have available today”. Even her article here differs from the biography in important respects. For example, it seems that Duchamp and the Baroness now no longer had a friendship between 1915 and 1917, or a “relationship” as she wrote in her introduction to the Baroness’s poems. So there is now no evidence that they knew each other before the exhibition at all. A big difference. There are plenty of others. We need not trouble the readers of the Burlington Magazine with any of these; we laid out the “facts” of this matter in the December 2019 issue, and a revised version can be found at atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/. There we have already explained Duchamp’s letter to his sister and other “mysteries” that Professor Gammel returns to in her article.

We do not wish to go over them again here, but to point out that Gammel’s thesis is also marred by a more basic misreading of the significance of Fountain in the history of Western art. With this object, Duchamp became the first to ask what the minimum requirements were for something to be considered an art work. He chose his readymades very deliberately to exclude all aesthetic considerations (which Norton and Stieglitz did not quite understand). He had to be indifferent to them in every possible sense, so that their status as an art object (or not) was reduced to this act of choosing, to the artist’s intention. This is the work’s meaning, subsequently acknowledged by art history, especially since the beginnings of conceptual art in the 1960s.

This meaning, clearly given it by Duchamp, and prefigured in his earlier notes, was initially expressed in Wood’s essay in The Blindman and soon afterwards by Breton’s in Littérature (1924). We do not accept that the Baroness had any role whatsoever in this object, but even if she had, it would be irrelevant historically because the significance of Fountain lies not in the object itself but in the conceptual meaning that Duchamp gave to it.

Fountain was not connected to Dadaism or “anti-art” as Gammel suggests. It was the first time an artist proposed the possibility of saying: “it’s art because I say it is” (to use the vernacular), an assertion which only gained traction some 40 years later. Thus when Gammel re-presents the Baroness’s dressing up as “performance art” (pps.170-174) and, in her edition of the Baroness’s poems, even appears to re-title a photograph of her from 1915 as a “Body Performance Poem”, decades before the existence of “Performance art”, she is making a retrospective re-categorisation that seems to us wholly illegitimate. The huge irony, of course, is that Gammel can only now see such things as art (mistakenly in our view, since the Baroness’s intentions are unknown) because of Marcel Duchamp’s original interpretation of Fountain. This was indisputably his innovation, and his alone, and it is the only reason why Fountain matters.

Dawn Ades & Alastair Brotchie

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 8b: Response to Gammel text 7.

This long piece by Gammel for The Burlington Magazine contained so little of immediate relevance that it does not really require a more detailed refutation than our published reply. But here are a few brief and rather impatient observations.

Paragraph 1: “Pissing contest”. Gammel has implicitly accused Duchamp of deliberately erasing the Baroness from an important moment in art history, in other words, of theft and lying. She should not be surprised that those who knew him or knew those who knew him should be a little unhappy with this! And if this text was really intended as an “open response” to her critics, it was much too late and contains far too little that actually engages with that critique. In fact, all four pages of this text appear to say as little as possible so as to avoid further pitfalls.

Paragraph 2. What has Thompson finding a replica of the original got to do with anything? It neither verifies the claim re either Duchamp or the Baroness nor refutes it.

Paragraph 3. What does Gammel mean by the word “intervention”? Is she referring to her changing the translation of this letter to his sister, already published in correct translations by both Naumann and Camfield? That looks like shoe-horning evidence to fit a predetermined narrative, and providing the French original next to a mistranslation (the only time the original language is given in her book) is strange in such circumstances, why did she not just use the existing translations — unless she was attempting to impose a different inflexion on this letter?

Paragraph 4 is full of speculations that one either finds convincing or not. We do not see anything scatological in either a urinal or a plumbing trap. And did very poor artists go about sueing exhibition organisers or anyone else at this time? As for R. Mutt meaning armut, our first page on this site has already shown the absurdity of this argument, perhaps Gammel might read it?

Paragraph 5 Not really relevant.

Paragraphs 6 and 7. Fountain was exhibited the same month as the first Dada show in Zurich. Duchamp has repeatedly stated it was at least another year before he knew anything about Dadaism, so Fountain was not made in this context and there was no Dada movement in New York at this time, properly speaking. Gammel then returns to her interpretation of readymades as ordinary objects that have been made aesthetic, in our view a significant misunderstanding of Duchamp’s intentions. The fact that Norton and Stieglitz were still “stuck” in such an interpretation means nothing. Wood, on the other hand, expressed very well Duchamp’s thinking about this, undoubtedy due to conversations with him.

Paragraph 8 “Facts themselves are part of what make up the regimes of truths.” So far as we can understand what this means, we agree, which is why our critiques have stuck to facts (taking a “regime” to be “an ordered way of proceeding”). If she means that facts are somehow authoritarian, does that mean she prefers “alternative facts”? That is the only alternative. If this paragraph is intended as a veiled critique of what we have written about her then Gammel needs to be a little more precise as to what “ideological apparatus” we are supposedly a victim of, or are promoting.

Paragraph 9. Those pesky facts again! Writing that something happened when it didn’t is not a metaphor! Fountain was not exhibited and she wrote that it was, how can that be considered a metaphor for something? It is either a lie or a mistake, and unfortunately Pofessor Gammel seems unable to admit she makes mistakes.

Paragraph 10. The translation of the letter. We agree with Bailey (and see para 3 above), that not everyone reads French and we wonder why the French was given here. If it was because she so unsure of her version, then why not have it accurately translated, or use the one of the two existing translations, because there is no ambiguity in the original?

Paragraph 11. No, there is no rationale dispute about the author. People helped him. This is not a difficult concept. Gammel fails to recognise that Norton’s involvement does erase the Baroness from the history of Fountain, because Norton says she never knew the Baroness, so in what way could the Baroness have been involved?

Paragraph 12. More mysteries! All Norton appears to have done is allow Duchamp to use her address, might she not have forgotten this in 50 years, or considered it uninteresting? It is clear from her interview that she though the whole affair was just a joke on Duchamp’s part. And to repeat for the nth time, there was no need for a go-between.

Paragraph 13. Not relevant.

Paragraph 14. Who signed Fountain? Who knows? But it was signed with a brush not a pen and any artist will tell you there is a deal of difference between the two. That said, all of the Baroness’s manuscripts have rounded Ms… If the handwriting does not much look like Duchamp’s that is hardly surprising since, to repeat what should be obvious, he was making a pseudonymous submission and so would have disguised his handwriting. Why the Baroness would be using a pseudonym at all goes wholly unexplained in the alternative versions of events.

Paragraph 15. “There is a belief that the Baroness had little contact with Duchamp before 1918.” Indeed, and this belief appears to be correct. The Baroness was destitute in Philadelphia for almost the whole of 1917 and there is no evidence they had met before then. Second part irrelevant.

Paragraphs 16 and 17. All irrelevant, since they concern matters after Fountain.

Paragraph 18 is also mostly irrelevant speculation, but the final citation from the Baroness: “M’ars [her name for Duchamp] came to this country […] to use its plumbing fixtures” seems to us to suggest that Duchamp is being identified here with Fountain, which is the opposite of suggesting that she had any claim to it!

*************************************************************************************************************

Finally, Spalding and Thompson replied to Gammel’s article in The Burlington Magazine (March 2021), and we replied to them in the same issue.

*************************************************************************************************************

Texts 9a, 9b and 9c.

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 9d, Response to Spalding and Thompson 9a and 9b.

We here respond to Spalding and Thompson at a little more length, but first point out that they have still not answered our critique of their version of events in the first page on this site nor shown any consequential link between the Baroness and Fountain.

Spalding’s Letter.

Paragraph 1. We are in almost complete agreement, Fountain was not a “collaborative exchange” with Marcel Duchamp.

Paragraph 2. The next two paragraphs are a mass of misunderstandings. So we will try to untangle certain aspects of this matter, not least for our own benefit, because some of Spalding’s arguments are beyond our comprehension.

— “Duchamp’s Urinal is not, really, a work of art at all because it cannot be seen.” First of all, Duchamp never made a work of art called Urinal, the work was called Fountain and it was submitted under the pseudonym of Richard Mutt, as was confirmed by its submission label. Secondly, as was explained in Beatrice Wood’s article, the whole point was to challenge what a work of art might be, and it is not up to Julian Spalding to decide that! Thirdly, what has the statement that “it cannot be seen” mean, and what has it got to do with its validity? We do not understand what point is being made here?

—“Many people imagine … that Duchamp exhibited a urinal so visitors could piss in it and, by inference, piss on the rest.” What people does he mean, and where’s the evidence? Given how much has been written about Fountain, it is surprising that, so far as we know, no one has ever suggested such a thing before! More to the point, Duchamp never envisaged exhibiting Fountain in this way, it was to be displayed on a plinth on its back, as it was photographed and as is made obvious by the orientation of the signature. Spalding is criticising Duchamp for something that he himself has invented. Which is odd.

—“When people see Duchamp’s Urinal they are confused because it does not look like a urinal, not at least one can urinate in.” This completely contradicts what he has just said in the previous paragraph but, no matter, we press on… So, to reiterate, there is no such work as “Duchamp’s Urinal”, it is called Fountain. Secondly, haven’t we just been told that it is not a work of art because it cannot be seen, yet now people are seeing it? As for the “confusion”, this arises because Duchamp recontextualised a urinal so that it wasn’t functional, which is exactly what he did with many of the readymades (Bicycle wheel, Coat Rack etc), except that Spalding doesn’t accept that this was a readymade… And the interpretation Spalding here attributes to the Baroness was not her’s, but Stieglitz’s and Norton’s, and to imply otherwise is more than a little dishonest. Furthermore, and most importantly, this interpretation is not now the reason why Fountain is considered important, but perhaps, like Gammel, he has not, after all, understood that?

Paragraph 3. And then it’s invisible once again, “Duchamp’s Urinal cannot be seen”: baffling! Next he criticises Duchamp for wanting to claim that “anything can be a work or art”, whereas the Baroness, on the other hand, wanted the “freedom to create art from anything”. What’s the difference? Why would the Baroness’s approach be acceptable, and Duchamp’s not? And why should it then only be Duchamp’s ideas that “lift artists above criticism”? And why should this be the case anyway? If it’s art, it can be criticised, isn’t that the job of art critics? And in what way would the Baroness have “created” this work if she had bought it from a plumber’s merchants, whereas Duchamp didn’t when he bought it? None of this makes a lot of sense.

Paras 4 and 5. Even Spalding himself seems unconvinced by his absurd pronouncements here! Bosch, Goya, Picasso, Freytag-Loringhoven. Is this really the new canon of Western art… ? One can over-egg a pudding.

And again, whereas Gammell imagines a urinal to be scatological (a rather disgusting thought), for Spalding it now appears to be sexual, even “magisterially” sexual, when moments previously it had been both Buddha and Madonna. Maybe a few more eggs won’t matter, because surely this must all be a joke?

Thompson’s letter

Paragraph 1. The fact that Glyn Thompson has spent 18 years trying to prove something which he has failed to prove is a tragedy for him, but a little boring for us. In only two short paragraphs he gives us any number of remarkable non-sequiturs and absurdities. Thus the two critics, McBride and Kobbé, we are told, were in a position to “know” that Fountain had been sent from Philadelphia. How were they in a position to know? As so often, Thompson does not tell us. He must have some unrevealed information, because neither of them wrote that the work was sent from Philadelphia, they both wrote that the artist was from Philadephia. In the context of this dispute, this is a very different matter. What we do know, from a letter of ca.10-14 April 1917, is that McBride was briefed by Charles Demuth, a close friend of Duchamp’s who was a part of the hoax, and he gave McBride the supposed artist’s phone number. It was Louise Norton’s, therfore in New York and not in Philadelphia. Furthermore, McBride lived until 1962, decades after Fountain was attributed to Duchamp, and so McBride joins the long list of contemporaries who never suggested they had the slightest suspicion that Duchamp was not the author of this work. And on the list of those who suggested otherwise? No one at all. A truly populous conspiracy of liars!

Paragraph 2. Thompson returns to the handwriting of the label and the signature. In fact he has failed to demonstrate that the handwriting on the label was the Baroness’s. It is quite evidently not in her usual hand, and Thompson has not explained why she would need to disguise it, since no one at the Independents knew her or her handwriting. The label and the signature on Fountain are indeed in different hands, but how does this support the Baroness’s involvement? And how could she have used Norton’s address when they did not know each other (a fact we have in Norton’s own words)? And, to repeat for the nth time, Duchamp would not have signed a pseudonymous submission in his own handwriting!

Finally, Hugnet’s attribution in 1932 was preceded by Picabia’s in 1919, and by another we have challenged Thompson to find (he too has not read our original text it seems). Furthermore, he also ignores the fact that, according to Irene Gammel, in the very article which he is supposedly responding to, the Baroness herself referred to Fountain twice in the early 1920s, in a painting and a poem, and both times in the context of Duchamp rather than herself, thus implying his authorship and not hers.

*************************************************************************************************************

When we entered this dispute, we assumed there must be some evidence to support its basic premise. Having soon realised that both of these party’s arguments were based only on speculation and wishful thinking, we then hoped to draw them into a reasonable debate. Finally, after much prodding, they at least replied, but only to continuously repeat their now disproven arguments and to ignore inconvenient questions they should have been able easily to answer if their version of events were correct. We have concluded that they are well aware they do not have any actual evidence to support their accusations, and since they will not engage meaningfully with specific critiques, all rational discourse has reached its logical conclusion.

We have no doubt that Spalding and Thompson will continue to peddle their absurd “theories”, and that those who do not want to check the facts, because such a narrative conforms to their prejudices, will continue to believe them.

Gammel’s position is more nuanced, but the central tenet of her version is not supported by any evidence so far as we can see, and to be taken seriously she really should produce some, Baudrillardian simulacra just will not suffice!

For our part we believe that we have refuted this counter-narrative by researching the facts, and that those who read what we have written and continue to believe otherwise are bracketing themselves with other rather more sinister conspiracy theorists. If that is the company they wish to keep, so be it, but if they imagine that there is anything feminist in this attempted re-writing of art history, then they have been duped. The Baroness was a remarkable woman who led an equally remarkable life, and it does not detract from her to maintain that she had nothing to do with something she never claimed authorship of: Duchamp’s Fountain.

To conclude, we would like to suggest what we believe actually happened at the Independents Exhibition, and the reasons for it, and in doing so briefly to move from facts to speculation (albeit supported by facts).

When the Independents Exhibition was set up it was to be jury-free, and naturally most of those on the committee did not consider it necessary to specify that submissions must consist of “art”, i.e. paintings, drawings, sculpture, etc. It seems to us, however, that certain of the committee members, or Duchamp at least, were well aware of what they were doing and had ensured such criteria were deliberately omitted in the hope that they would receive some much more outrageous submissions. Yet this did not happen, precisely because, before Fountain, it was impossible for anyone to think of doing so. Fountain was the first such object, and on this depends its art historical importance. And so, all of these avant-garde artists from around the world dutifully submitted their more or less conventional paintings and sculpture. A few days before the exhibition opened, Duchamp and a few of these friends had a discussion in which they reviewed this disappointing situation — after which he purchased and submitted Fountain. It was an act of last resort, undertaken because it simply had not occurred to anyone else to do such a thing. It seems, according to Norton, that Duchamp was genuinely angry when it was refused, since he was hoping for a furore in the press to match that of the Armory Show four years earlier. All he could do was resign and try to foment a scandal that way instead. He needed two things in order to do so, firstly a press photograph of Fountain, and secondly he and his collaborators needed a “story”, both to make the newspapers bite, and so as to avoid all and sundry discovering he was behind the affair, in which case there would be no newspaper story and no scandal. In the event they had two, “the young lady” for friends, and for the Press: “the man from Philadelphia”. Despite the committee’s refusal to show it, Fountain eventually changed everything, even though no one realized it at the time.

The Baroness, magnificent as she was in so many ways, played no part in any of this.

Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie

ORDERING DURING THE VIRUS

We would like to thank all those who have been ordering books despite the warning on our site that we may not be able to mail them in the near future. We are doing our best and we hope to resume mailing within a week and to clear our backlog, and then to mail every couple of weeks. This is dependent on the local post offices remaining accessible, but this does not seem unlikely.

Unica Zürn THE MAN OF JASMINE

This title is pretty much ready for print, but we have delayed publication due to the current situation, we now aim to publish in November.

NEW TITLE now available

The Journal of the LIP 21: The Brothers Quay. The Quays seen through their passion for calligraphy and marionettes. Texts and photos by the Quays, an astonishing and beautiful sixteenth-century calligraphy manual, and Jarry’s texts on marionettes. For a complete description click the page link.

For information about subscribing to the Journal of the London Institute of ’Pataphysics, please contact Lucky Roberto at patasec141@gmail.com.

CAMPAIGN: MARCEL DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS

A second page of letters by Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, this time from the Art Newspaper, contest the claims that Duchamp stole his readymade “Fountain” from the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Some of the protagonists (Spalding and Thompson) here hazard a reply, whose inadequacies are quickly demonstrated. The originator of this allegation, Professor Irene Gammel of Ryerson University, continues to maintain her silence.

Our text in The Burlington Magazine, constituted a detailed critique of the evidence presented by Spalding and Thompson to support their contention that Duchamp stole Fountain from the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Neither they nor Irene Gammel responded, so we published two follow-up letters in the Art Newspaper, which are reproduced below, followed by the responses of Spalding & Thompson, and by our replies to them.

CONTENTS OF THIS PAGE

PAGE 2: MARCEL DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS

[Texts 2: Emails from Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie to Irene Gammel appear on Page 3]

Texts 3. Letters to The Art Newspaper, 320, February, 2020, and our responses.

3a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Did Duchamp really steal Elsa’s urinal?”

3b. Julian Spalding, “It’s the world’s first great feminist, anti-war artwork”.

3c. Glyn Thompson, “No grounds for Ades’s view”.

3d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. Replies to 3b and 3c.

Text 4. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 322, April 2020. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Urinal Row Rages On”.

***********************************************************************************************************

Text 3a: THE ART NEWSPAPER, 320, FEBRUARY 2020

“Did Duchamp Really Steal Elsa’s Urinal?”

by DAWN ADES and ALASTAIR BROTCHIE

In November 2014, The Art Newspaper published an article by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson called “Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s urinal?” Their contention was that the artist and poet the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was responsible for submitting the famous Fountain, an upturned urinal signed R.Mutt, to the Independents exhibition in New York in April 1917. These assertions appeared to confirm the worst suspicions concerning the art-world patriarchy, and so have become widely distributed on the internet.

This controversy was recently revived when, in November and December, two articles in The Burlington Magazine, by Bradley Bailey and another by ourselves, refuted these assertions in great detail. An updated version of the latter, a summary of the facts, can be found at https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/. Spalding and Thompson have yet to respond in a reasoned manner, and Spalding’s website continues to call Duchamp a thief and claims that “The Art World has been lying to us”: classic conspiracy theory rhetoric (note the capitals!).

Spalding and Thompson have never produced any evidence that connects the Baroness with Fountain; only interminable speculations about what might or could have occurred if their theories happened to be true. These speculations have been refuted or shown to be unproven in the articles mentioned, but they are all anyway irrelevant unless Spalding and Thompson can answer the only question that matters: “What evidence connects the Baroness to Fountain?”

If they cannot provide this evidence then their only honourable course of action is to admit they were wrong, or must be presumed to be deluded. However, we recall the old saying: “Reasoning will never make a man correct an ill opinion, which by reasoning he never acquired”. We are not holding our breath!

******

This was accompanied by texts by Spalding and Thompson (texts 3b and 3c)

OUR RESPONSE TO THE ABOVE (text 3d)

We asked a question: “What evidence connects the Baroness to Fountain?” Neither Spalding nor Thompson answered it.

******

Our reply to Spalding:

A detailed reply to Spalding’s cursory response is obviously unnecessary since it consists mostly of his own opinion, and we are interested in facts. He also appears not to have understood our question, because the only facts he refers to (Duchamp’s letter and the availability of the urinal), do not at all connect the Baroness to Fountain. Furthermore, Spalding and Thompsons interpretation of these pieces of “evidence” has been shown to be unproven and/or unreliable in our previous article (text 1).

******

Our reply to Thompson:

Thompson’s reply to our letter repeatedly addresses only one of its authors: a basic incivility, and like Spalding, he does not answer the question we actually asked. We shall go through his response in detail, and we ask him again to afford us the same courtesy with regard to our previous article (in its revised version as published on this website).

***

We have never claimed that there is much in the way of documentary evidence from April 1917 that Duchamp was responsible for the urinal since it was submitted pseudonymously, but there is a huge amount of subsequent and contextual evidence that does exactly that, in particular Louise Norton’s interview and her article published by Bailey (a refutation of Spalding and Thompson’s argument that they have yet to comment on).

By the same logic – you can’t have your cake and eat it – what evidence, then or afterwards, connects the Baroness with Fountain (the question we asked)?

Even so, evidence connecting Duchamp is not entirely lacking. Alfred Stieglitz, for one, certainly suspected (or perhaps knew of) Duchamp’s involvement from the start, he wrote to Georgia O’Keeffe on 19 April 1917: “There was a row at the Independents – a young woman, (probably at Duchamp’s instigation) sent a large porcelain urinal on a pedestal to the Independents…” (The Baroness, incidentally, was 43 at the time.)

***

Duchamp’s letter to his sister can be interpreted in various ways of course, as we have previously shown. We return to this letter below.

***

Thompson writes that “Due diligence … demonstrates that the first citation [that Fountain was by Duchamp] was by Georges Hugnet … in 1932” etc. This would be unsurprising because Hugnet was the first serious French historian of Dada. However, we have never once mentioned Hugnet in any of our texts on this matter, and what he wrote is irrelevant to our disagreement with Spalding and Thompson.

More relevant is that Mr Thompson is wrong.

The first mention of the urinal in connection with Duchamp that we are aware of dates from February 1919. Francis Picabia, in his regular news bulletin of what his friends were up to, in 391 (no.8, p.8), wrote: “Marcel Duchamp parti à Buenos-Ayres pour y organiser un service hygiénique de Pissotières – Rady-made [sic]” (Marcel Duchamp left for Buenos Aires to organise a hygienic service of urinals – Rady-made). Thus Fountain was identified as a readymade soon after its exhibition – Spalding and Thompson have repeatedly denied that Fountain was a readymade (e.g. in The Jackdaw, 4.7.2015, p.7), because that would mean it was by Duchamp.

But we note too that André Breton, in his essay “Marcel Duchamp” (Littérature 5, October 1922, p.9), alludes to these words from the editorial in The Blind Man (May 1917) on Fountain: “Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it.” Breton commented: “… the personality of choice, whose independence Duchamp is one of the first to announce by signing, for example, a manufactured object…”

There is, by the way, at least one other mention before Hugnet of the urinal being by Duchamp, which we will leave to Thompson to diligently discover!

***

Thompson then refutes two phrases which we assume are citations from Hugnet: “in order to test the impartiality of the jury” and “Duchamp had wished to signal his disgust for art and his complete admiration for ready-made objects”. The fact that Hugnet is perhaps wrong is completely irrelevant, in a reply to our letter, unless we said he was right.

We did not say that, and it is dishonest of Thompson to imply that we did.

***

His next point is that the handwriting on the exhibition label was not Louis Norton’s. However, her statement cited in Bailey’s article is clear: Duchamp “sent it [Fountain] in”, all Duchamp needed was permission to use her address, why would he need her handwriting?

The question of the handwriting is irrelevant, as we have already pointed out in our previous article.

***

Bailey is then criticised for “introducing into the practice of provenance the innovative concept that the absence of a signature from a work of art proves its authorship.”

Is it too blindingly obvious to point out to that Thompson does precisely the same thing, since the Baroness’s signature is likewise absent?

***

We have never written or implied that Duchamp’s sister “put it about the New York art scene that Duchamp was not responsible for the work” or even that she put it about that he was responsible. This is another invention of Thompson’s. We merely pointed out that she was in a relationship with the artist Jean Crotti, and that he was on familiar terms with a large number of the people directly involved, and with significant others in the avant-garde, especially Picabia. Thompson’s “contextualisation” of Suzanne as a “nice petit bourgeois provincial, with no profession” seems a little patronising from a professed feminist: she had temporarily signed up as a (war-time) nurse but was also working as an artist. Indeed, Duchamp, in the very same letter, asks about her work and suggests he might get her an exhibition in New York if her work is “not too difficult to ship”. In this letter he is simply telling her what is going on while not revealing his own involvement – it was news to be passed on to friends and family (one of their brothers had a work in the Independents exhibition) – and Duchamp was preserving his anonymity for the reasons we have given in our previous article.

Thompson states that “Ades’s position … assumes that Suzanne had contacts in New York”. It does not assume that at all. It assumes that persons to whom Duchamp actually asks Suzanne to pass on the contents of his letter (“Tell the family this snippet”), had contacts in New York or the international avant-garde, and just to spell it out, these persons were principally Jean Crotti, her lover, but also her brother, Jacques Villon.

***

He then states: “there is no record that anybody suspected … Duchamp of having anything to do with the urinal”.

Wrong: see the letter from Stieglitz and the comment from Picabia mentioned above.

***

In his final paragraph he asserts “that only members could show” works at this exhibition and that therefore Thompson’s critics, those heinous supporters of conceptual art, have confused the “‘no jury’ rule with a carte blanche to show anything”. This is because “they didn’t bother to read the publicity issued by the society that made it explicit that only members could show.” Thompson is determined to disprove that artists could submit anything, because it was to test this policy that Duchamp submitted Fountain.

So it is important that “the publicity” does not support what Thompson claims. The catalogue of the Independents exhibition clearly states: “There are no requirements for admission to the Society save the acceptance of its principles and the payment of the initiation fee of one dollar and the annual dues of five dollars. All exhibitors are thus members…” (Archives of American Art). So yes, you had to be a member, but to become a member you simply had to pay six dollars and then, since there was no jury, you could indeed submit whatever you liked, just as the first line of the editorial in The Blind Man 2 implied: “They say any artist paying six dollars may exhibit.”

So Thompson is wrong again.

***

We have felt obliged to reply to Thompson’s criticisms of our position. We will be very reluctant to do so again until he answers reasonably and succinctly the two questions we have asked in our follow-up letter to the Art Newspaper, which is posted below.

Dawn Ades & Alastair Brotchie

***********************************************************************************************************

Text 4: THE ART NEWSPAPER, 322, APRIL 2020

“Urinal Row Rages On”

by DAWN ADES and ALASTAIR BROTCHIE

Last month we wrote a letter to this paper about the suggestion by Spalding and Thompson that Duchamp stole his readymade Fountain from the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. They replied as expected. Mr Spalding was cursory, and the only “evidence” he presented was his own opinion. This response merits no further comment. Thompson’s reply was prolix, but where not irrelevant, it consisted of arguments we have already refuted, and refutations of arguments that we never made. His assertions are easily disproved.

Last December we published a detailed critique of Spalding and Thompson’s accusations in The Burlington Magazine and this — along with our refutations of Thompson’s rely to our letter in the Art Newspaper last month — can be consulted at: https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/. Spalding and Thompson have so far refused to respond to our original article yet continue with the same arguments.

Here we wish to concentrate on the real crux of the matter. We have reduced this argument to two questions which Spalding and Thompson should be able easily to answer if their accounts are correct:

1. Setting aside what Duchamp did or didn’t do, what facts connect the Baroness to Fountain? So far as we can see the only connection cited by Spalding and Thompson or by Gammel is that an unknown journalist, and not exactly a “serious” one, and then some other journalists, wrote that Richard Mutt lived in the same city as her, Philadelphia. Is that it?

2. Almost the only undisputed fact in this affair is that Louise Norton’s address was on the submission label attached to Fountain: this fact is agreed by Gammel, by Spalding and Thompson and by those who accept Duchamp’s account. Thus Louise Norton is the only person whose pivotal role as go-between is acknowledged in all three versions of these events, and because of this role, she had to know what actually happened. In a text recently discovered by Bradley Bailey, she wrote of Duchamp: ‘To test the bona fides of the hanging committee he sent in a porcelain urinal which he titled, Fountain by R. Mutt. The committee promptly threw it out and Marcel very angry promptly resigned’. This statement on its own proves that Spalding and Thompson are wrong. Is this not the case?

It should be noted, however, That this statement was not available to Gammel in 2002 when she published her biography of the Baroness, which is the source of this rumour against Duchamp. So, since the welcome aim of restoring agency to forgotten and overlooked women artists is not served by misinformation, now is perhaps the appropriate moment for her to comment on this controversy?

***********************************************************************************************************

These two questions went unanswered. The repeated refusal especially of Spalding and Thompson to respond to a detailed criticism of their version of events demonstrates that they are unable to defend their position, and this refusal can only be taken as an admission that the facts have proved them wrong.

***********************************************************************************************************

At this point we wrote that we were awaiting developments in July, since after a great deal of persuasion we had heard that Professor Gammel had finally decided to break her unexplained silence. Why she did so will be revealed on the following page.

NEW TITLES

After various delays due to setting up new printing arrangements, we can finally announce two new titles. Follow the links for a more complete description.

Now published:

The Journal of the LIP 20: Alfred Jarry et al THE INSTRUMENTS OF THE PASSION: THE NAILS AND THE BICYCLE.

Jarry and The Passion of Christ, treated pataphysically it goes without saying…

And more recently

Unica Zürn THE HOUSE OF ILLNESSES

Originally published as a part of our series of small publications, The Printed Head, in 1994, this is not a reprint but a completely re-originated version of this illustrated text which reproduces the whole manuscript in colour facsimile with the translation by Malcolm Green interleaved.

Some spreads:

A CAMPAIGN: MARCEL DUCHAMP WAS NOT A THIEF

Many of you will be aware that there is supposedly a controversy concerning the authorship by Marcel Duchamp of the artwork Fountain, a urinal turned on its back and signed R.Mutt, which is generally considered a founding work of conceptual art, and which certain persons have attributed to the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. This controversy originated with speculations in the biography of the Baroness by Irene Gammel. It was expanded upon in an offensively belligerent manner, as part of their campaign to discredit conceptual art, by Julian Spalding Spalding and Glyn Thompson, who added to it a completely spurious feminist gloss. This has been persuasive enough for those who have not bothered to check their “research” to teach these speculations as proven facts in higher education institutions, and for them to feature in a recent novel by Siri Hustvedt, Memories of the Future.

The article here, by Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, considers the real facts of this affair and finds that they conclusively refute the reattribution of Fountain to the Baroness.

This article has been emailed to those involved: Irene Gammel, Julian Spalding, Glyn Thompson, David Lee (editor of The Jackdaw). All have so far refused even to acknowledge receipt of this text, let alone refute its conclusions.

Atlas Press will be publishing an expanded version of this text later in 2020 and we hope to include the reaction of those involved. We believe that a continued silence on their part can only constitute an admission that they were wrong.

We wish to circulate this text as widely as possible — a wrong has been done here — and invite the recipients of our mailing list to help us to do so.

NEXT

A new revised edition of THE MAN OF JASMINE by Unica Zürn will appear early in 2020.

This is the first of three pages on this site devoted to the accusation by Professor Irene Gammel, and then by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, that the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was involved in the creation of “Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp — indeed, according to Spalding and Thompson, that he actually stole it from her.

Following letters from Dawn Ades in The Guardian and from Alastair Brotchie in The Times Literary Supplement, objecting to repetitions of this unproved allegation, we decided to join forces to refute it factually. By chance, it was around this time that we discovered that Bradley Bailey had found important new information that he was about to publish in The Burlington Magazine (161, October 2019). The same issue therefore included our detailed summary of the factual evidence to date (and this version of it has been updated to include Bailey’s discoveries) and it was hoped that this text would launch a debate between all protagonists based around facts rather than suppositions.

This summary remains the most detailed survey of the facts, along with critiques of the alternative accounts based on these facts.

Here are the complete contents of the pages that follow:

PAGE 1: MARCEL DUCHAMP WAS NOT A THIEF https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/

Texts 1. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief”, The Burlington Magazine, December 2019, (an overall summary of the controversy, below).

PAGE 2: MARCEL DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-and-the-baroness/

Texts 3. Letters to The Art Newspaper, 320, February, 2020.

3a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Did Duchamp really steal Elsa’s urinal?”

3b. Julian Spalding, “It’s the world’s first great feminist, anti-war artwork”.

3c. Glyn Thompson, “No grounds for Ades’s view”.

3d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. Replies to 3b and 3c.

Texts 4. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 322, April 2020. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie, “Urinal row rages on”.

PAGE 3: DUCHAMP AND THE BARONESS: END OF THE FOUNTAIN AFFAIR

https://atlaspress.co.uk/duchamp-and-the-baroness-end-of-the-fountain-affair/

Texts 2: Emails from Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie to Irene Gammel.

2a. Email of 26/11/19.

2b. Email to 9/12/19.

2c. Letter of 6/1/20.

2d. Email of 23/1/20.

Texts 5. Irene Gammel. “Last word on the art historical mystery of R. Mutt’s Fountain?”, The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020.

Texts 6. Letter to The Art Newspaper, 326, September 2020, and expanded response.

6a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The last word? Not likely…”

6b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 5)

Texts 7. Irene Gammel. “Plumbing fixtures: The vexing and perplexing case of R. Mutt’s ‘Fountain’” in The Burlington Magazine, January 2021.

Texts 8. Letter to The Burlington Magazine, January 2021, and expanded response.

8a. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “The Authorship of ‘Fountain’”, (reply to 7).

8b. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to Irene Gammel (Text 7).

Texts 9. Letters to The Burlington Magazine, April 2021, and expanded response.

9a. Julian Spalding. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text7).

9b. Glyn Thompson. “‘Fountain’, Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven” (reply to Gammel, text 7).

9c. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. “End of the Fountain controversy”, reply to Spalding & Thompson, 9a and 9b.)

9d. Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. More detailed response to 9a and 9b.

We leave it to readers to decide if Gammel and Spalding and Thompson have answered our challenge to their different allegations.

*************************************************************************************************************

Text 1: The Burlington Magazine, December 2019 (with subsequent small modifications)

“Marcel Duchamp Was Not a Thief”

by DAWN ADES and ALASTAIR BROTCHIE

***

Notes are at the end. This article is being updated (our thanks for corrections from Francis Naumann) in order to make it the definitive account of this affair. The reader will see, as the correspondence unfolds, that neither Irene Gammel, Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, nor David Lee, editor of The Jackdaw (who expressed his agreement with Spalding and Thompson when he published them), have responded to any of the specific points in this account that dispute their versions.

*************************************************************************************************************

In November 2014 The Art Newspaper published an article by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson, ‘Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s urinal?’1 Their contention, and that of Irene Gammel, the biographer of the artist and poet Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, is that the Baroness was responsible for submitting the famous Fountain, an upturned urinal signed ‘R. Mutt’, to the Society of Independent Artists (SIA) exhibition in New York in April 1917.

The idea of Duchamp as an ‘art-thief’ has become something of an internet meme – accepted as true, without anyone ever bothering to check the evidence. Refuting it then becomes a matter of proving a negative, which is much harder to do. We are well aware that facts and evidence can be rather less amusing than speculation and conspiracy theories, but there is a truth to be revealed here that relates to the integrity of one of the most important artists of the last century, and an artwork frequently judged the most important of the last 100 years. This truth has been carefully obscured by a blizzard of irrelevant research by Spalding and Thompson, the intention of which appears to have been to conceal the fact that no serious evidence whatsoever has been presented that links the Baroness to Fountain. Moreover, Bradley Bailey’s article in The Burlington Magazine published evidence that finally put paid to their speculative contentions. These contentions nonetheless need to be dealt with, and following Bailey’s article we wanted to summarise the facts of this affair.

There are three versions of the events that gave rise to this ‘sculpture’: firstly, the generally accepted account, based on what Duchamp himself said, and accounts by eye-witnesses, the perpetrators and contemporary publications; secondly, Gammel’s speculations in her biography of the Baroness; and thirdly, Spalding’s and Thompson’s account, which attempts to claim Fountain for the Baroness while avoiding the inaccuracies in Gammel’s version.

***

According to Duchamp’s biographer,2 the idea for the urinal was due to a last-minute impulse. Following a lunch together, and just before the SIA exhibition was about to open, Duchamp, accompanied by Walter Arensberg and Joseph Stella, bought a urinal at a store, and he either took it to his studio or directly to the exhibition venue, signed it ‘R. Mutt’ and attached a submission label bearing the address of Louise Norton. It was then submitted for exhibition, but never was exhibited. Instead it was taken to Alfred Stieglitz’s studio so he could photograph it.3 Duchamp used the inevitable scandal (which would have occurred whether the exhibit was accepted or not) and Stieglitz’s photograph to explain the rationale behind readymades in the magazine The Blindman, again anonymously, through an article by his friend Beatrice Wood.4 Thus two of Duchamp’s female friends collaborated in this affair: Norton and Wood.

***

Gammel’s version is that the Baroness may have sent the urinal to Duchamp, who put it in for the exhibition. He then used the scandal to explain readymades. She casts doubt on Duchamp’s authorship of Fountain on the basis of a letter from Duchamp to his sister Suzanne, dated 11th April 1917. The relevant part of Duchamp’s letter reads:

Tell the family this snippet: the Independents opened here with enormous success. A female friend of mine, using a male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, submitted a porcelain urinal as a sculpture. It wasn’t at all indecent. No reason to refuse it. The committee decided to refuse to exhibit this thing. I handed in my resignation and it’ll be a juicy piece of gossip in New York.5

Gammel translated this letter so that the pivotal sentence reads: ‘One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture’.6 Gammel then tentatively identified the ‘female friend’ as the Baroness, based solely on the fact that, according to a journalist, Mutt lived in Philadelphia (see note 23 for the text), as did the Baroness. Gammel suggests that the Baroness may have sent the urinal to Duchamp, and that it therefore might have been ‘a collaboration’.7

Gammel’s interpretation is mistaken. The letter actually says that Fountain was submitted to the SIA in the category of sculpture, and not sent to Duchamp personally. No one knows why the journalist gave the artist’s home as Philadelphia,8 and his article is unreliable as a source, because even though it is very short it contains several other blatant errors or inventions.9 There is, furthermore, a version of Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph of Fountain (Fig.2) in which the submission label is visible and the artist’s address is clearly legible. The address is not that of the Baroness but of Louise Norton. Gammel relegated this important information to an endnote.10 The writing on the label is not Louise’s,11 but Duchamp could have asked anyone to fill it in using Norton’s address, or could have done it himself and disguised his handwriting.12 Finally, Norton’s involvement was further confirmed when it was discovered that the phone number for contacting Mutt given to the critic Henry McBride by Charles Demuth, was hers.13 Gammel does not mention this fact at all.

***

While Spalding and Thompson acknowledge that their version is based upon Gammel’s research,14 they need a different story in order to avoid its shortcomings, namely her ignoring the evident part played by Norton, and her incorrect translation of the letter. So they speculate that the Baroness (then famously close to destitution) buys the urinal in Philadelphia, presumably signs it (while disguising her handwriting, even though her handwriting would be unknown to anyone involved), and then has it sent to Norton, who adds the label and submits it. Duchamp then ‘steals’ it and uses it to explain readymades. Thus the whole of their case depends on the Baroness and Norton knowing each other, and they baldly state that Norton ‘knew Elsa well’.15 No source is given for this statement, and Bailey has revealed in his article that, according to Norton’s own words, she did not know the Baroness. The Spalding and Thompson version cannot, therefore, be correct.

Spalding’s and Thompson’s evidence for their version is the letter to Suzanne; the Philadelphia connection; and the assertion that Duchamp’s account of how he bought the urinal is incorrect (based on Thompson’s research intended to prove that the firm of Mott did not make this model of urinal, etc.).

The evidence against it is as follows: Spalding and Thompson repeatedly use the letter as evidence that Duchamp ‘lied’ about the origins of Fountain. In fact, Duchamp told his sister exactly what friends in the New York art scene who were not in on the hoax were allowed to know. Stieglitz repeated precisely the same story in a letter to Georgia O’Keefe, and the previously mentioned letter from Demuth to MacBride does essentially the same.16 Spalding and Thompson criticise Duchamp’s biographer’s interpretation of the letter to Suzanne:17 ‘Tomkins [. . .] argues that Duchamp wanted (for reasons he doesn’t explain) to keep his involvement in the “affair” of the urinal secret. This was why he pretended in his letter to his sister that a “female friend” had submitted the object. But this explanation makes no sense because his sister, a Red Cross nurse in Paris, had no contacts with the New York media’.18

However, Tomkins is correct and Spalding and Thompson are wrong. There is no mystery as to why Duchamp needed to keep his identity secret. He was on the board of directors of the SIA exhibition and head of the hanging committee, and if he had submitted the urinal under his own name then some way would have been found to defuse the situation, and avoid the scandal he was intent upon, as he explained in an interview in 1966.19 As for the assertion that the artist (rather than ‘the nurse’) Suzanne Duchamp was not in touch with the New York art scene (rather more important than the “media” in this context), her partner in Paris was Jean Crotti, soon to be her husband, who in 1916 had shared a studio with Duchamp in New York. Crotti had lived there for several years, and had been a habitué of the Arensberg salon. He was on amiable terms with many of those involved with the exhibition, as well as with members of the wider international avant-garde.